I’ll start with an anecdote. Recently, while walking my dogs in a residential part of West Campus, I came across a partially demolished house lot with several realtor signs in the front yard. Inside the structure, a team of laborers worked to destroy a wall with hammers, shouting instructions to each other in rapid Spanish; outside, a man in a suit and tie stood leaning against a pillar, negotiating a lunch order on his cell phone. I watched them for awhile, not noticing as another dogwalker passed by and his leashes became tangled up with mine. I apologized, but the stranger, politely waving away my worries, merely pointed at one of the realtor signs, saying: “Californians, right?” We both laughed. It was a short, patently unimportant interaction between strangers, yet in the stranger’s two words – “Californians, right?” – there was a whole world of meaning to unpack.

Most Austin Area residents will have at some point heard “Californians” used this way, as a catch-all explanation for Austin’s reckless growth in recent years. Californians, so the rumor goes, are speculating in Austin’s real estate market, driving prices up at the expense of actual local home buyers. Can’t find a job? Silicon Valley firms are invading Central Texas and bringing their (Californian) employees with them. High cost of living? Blame Californians. Rush hour traffic? Blame Californians. Your favorite bar is crowded? That taqueria near your apartment closed? Ask an Austinite to list their woes and, invariably, Californians will crop up at some point as a direct or indirect source of blame.

While I may be exaggerating the severity and extent of Austin’s fixation on Californians, most longtime Austinites will be at least vaguely aware of what I’ll dub the “California Narrative”: a locally-held belief that the migration of Californians to Central Texas is changing the Austin Area, largely for the worse. This is a belief observers in both California and Texas have noted and written about as far back as the 1990s, and, in my experience, it is a frequent topic of casual debates in coffee shops and taco bars across the Austin Area. In this blog post, I’d like to contribute to this running conversation while looking beyond the anecdotal evidence it is usually accompanied by; instead, I will attempt a data-driven approach to the issue, utilizing the Austin Area Sustainability Indicators’ robust collection of primary and secondary data.

Though it comes in many forms, the “California Narrative” basically rests on two key assumptions: (1) that Californians are migrating to the Austin Area in large numbers and (2) that these recently arrived Californians have driven, or are entirely responsible for, drastic changes to Austin’s economy and culture. The validity of the first assumption can be easily assessed using migration figures obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau. According to U.S. Census Population Estimates survey, Austin was the fastest growing major city in America between 2010 and 2017.1 Analyzing this data, Chris Ramser of the Austin Chamber of Commerce found that 56.2% of Austin’s population growth during this period was due to domestic migration – migration to Austin from other locations within the United States – rather than international migration or natural population increase. 2 Recent migrants to Austin (both foreign and domestic) made up 12.9% of the city’s population over the 7-year period, the highest such proportion measured for any of America’s 50 largest Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) during that time. Taking into account that an overwhelming percentage (82%) of Austin’s positive net migration over that period was due to domestic migrants, this data suggests that recent domestic migrants – Californians included – make up a higher proportion of Austin’s population than they do in other cities. In other words, domestic migrants are more noticeable in Austin than they are in other major American cities, statistically speaking.

Unfortunately, the Population Estimates program doesn’t track migrants’ specific places of origin, so there’s no way of knowing how influential Californians are within the larger population of Austin’s domestic migrants. We can, however, approximate this proportion using a different data source, the Metro Area-to-Metro Area Migration Flows estimates conducted by the American Community Survey. According to the most recent available ACS data, a resounding majority of domestic migrants to Austin between 2012 and 2016 hailed from other Texas MSAs (53.2%). 5.63% of domestic migrants over the same period of time came form California MSAs, making California the second-most common source of migrants to Austin ahead of Florida (3.6%) and New York (3.0%). Ranking migrant’s MSAs of origin by number of migrants to Austin, San Francisco-Oakland (1,364) and Los Angeles (2,702) both make the top ten, but are well behind the top three cities San Antonio (9,959), Dallas-Fort Worth (11,449) and Houston (13,987). Texans, not Californians, are the most influential factors behind Austin’s recent population growth.

So, Austin is getting more expensive, but are Californian newcomers to blame? Probably not. As already demonstrated, Californians make up a relatively small percentage of migrants to Austin. Even if Californian migrants to Austin are on average wealthier than their non-Californian counterparts – not a dubious proposition, considering that many of Austin’s Californian migrants are well-salaried members of the tech sector – it’s very unlikely that such a small group of people could be responsible for such extreme price changes.

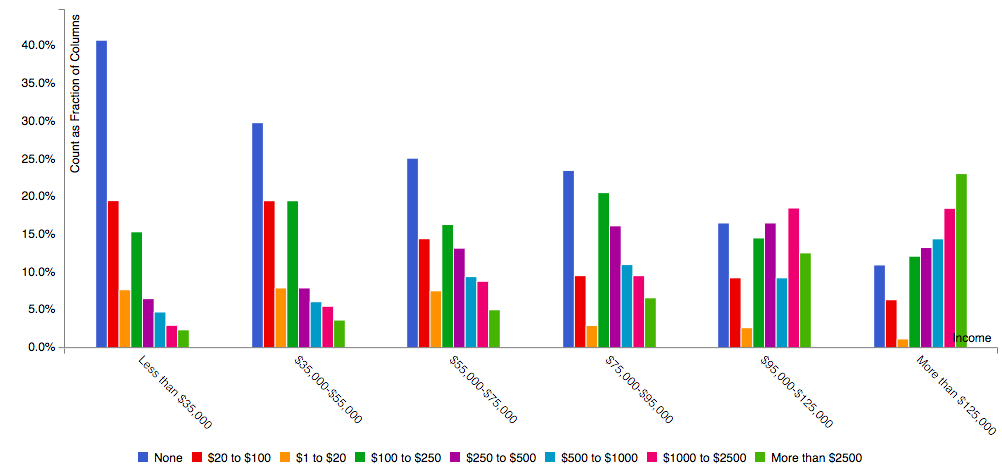

Proving that Austin’s culture has changed is even harder to do with data: can such a thing even be measured? The 2018 Austin Area Community Survey conducted by A2SI found that Austin Area residents were likely to express satisfaction with the region’s arts communities. While the same survey noted declining rates of volunteerism and individual philanthropy in the Austin Area, the region still has a high level of overall civic health, with each of the regions’ six counties except for Caldwell regularly recording midterm voter turnout rates above the statewide average [HTML citation]. One worrying trend is a growing income-based disparity in civic engagement, with Austinites from higher-income families being more likely to participate in civic affairs than their less affluent fellow citizens. For example, while the overall rate of individual giving recorded by the Austin Area Community Survey decreased from 88% to 75% between 2015 and 2018, the percentage of respondents who donated more than $500 per year actually increased from 23% to 29%; during the same three-year interval, the percentage of individuals who donated less than $500 per year decreased from 65% to 46%. 89% of Austinites from households with incomes of $125,000 or more before taxes reported making charitable donations, versus 76% of Austinites from households making $75,000-$95,000, 70% from households making between $35,000 and $50,000, and 60% from households making less than $35,000. Similarly, Austin Area residents from households making $95,000 or more per year report participating in civic affairs at higher rates then less affluent Austin Area residents.

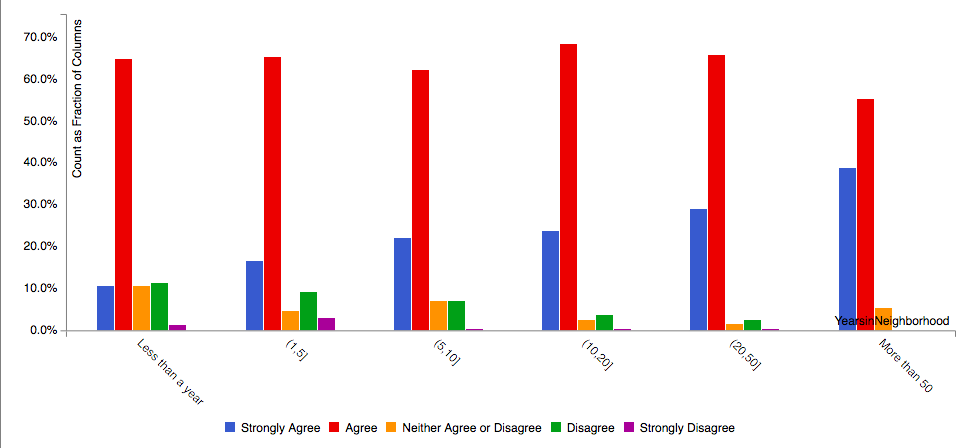

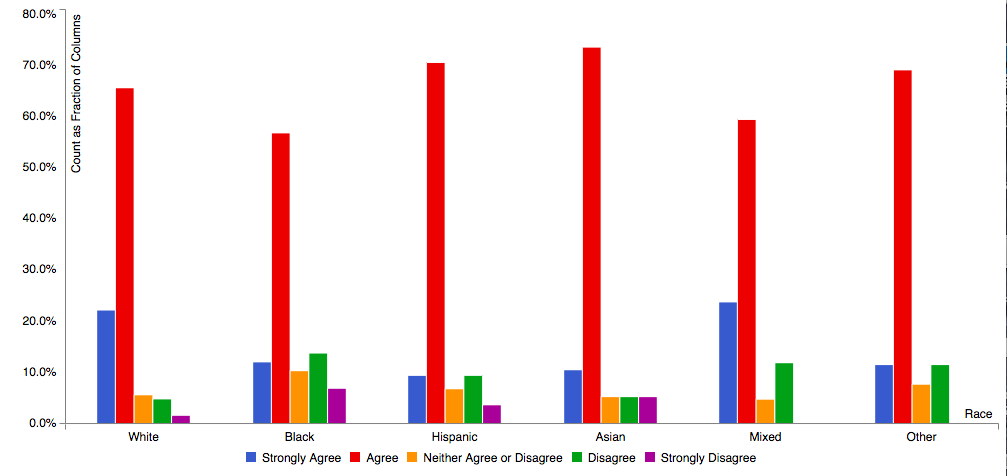

So: Austin is getting more expensive, and Austin is exhibiting some signs of a weakening culture – diminishing social cohesion and civic engagement – but are Californians really to blame? The data suggests that they are not. In fact, there’s very little in the data collected here suggesting that newly minted Austin Area residents differ at all from locals in their attachment to the region. However, we can’t discount the California narrative. Cultural myths, even specious ones, are invaluable objects of study because they reflect the beliefs and feelings of the societies that produced them. The sheer popularity of the California Narrative suggests that Austin Area residents are deeply aware of, and worried about, the changes the region is undergoing. Californians may not be changing Austin, but Austin is changing. Hopefully, the public discourse surrounding these issues can move on from attributing blame to developing long-term, holistic solutions.

Endnotes

[1] This data can be downloaded here

[2] Ramser’s calculations, which can be found in this article, differ slightly from mine at times because Ramser excluded domestic migration to and from Puerto Rico.

[3] Texas A&M University Real Estate Center, Housing Activity and Affordabliity: Price Distribution, https://www.recenter.tamu.edu/data/housing-activity/.

[4] Glasmeier, Amy K. & MIT, Living Wage Calculator, http://livingwage.mit.edu/metros/12420.

Image created by “Organic Local Austin Memes.” Available here (warning: much of the content on this Facebook page is NSFW).

Magnificent website. Lots of useful info here. I’m sending it to a few friends ans also sharing in delicious. And obviously, thanks for your sweat!

Excellent blog! Do you have any helpful hints for aspiring writers? I’m hoping to start my own site soon but I’m a little lost on everything. Would you suggest starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a paid option? There are so many options out there that I’m completely overwhelmed .. Any ideas? Kudos!